People have lived in the Toronto region on the north shore of Lake Ontario for almost 11,000 years since the first indigenous people moved here from the south after the ice age. Direct contact with Europeans occurred in the 17th century, and the French built small trading posts here

during the 18th, but the birth of the urban community did not occur until the British regime. In 1787, the Toronto area was purchased from the Mississaugas; then in 1793, John Graves Simcoe, lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada, established a military post and civilian

town to improve the colony's defences during a period of threatened American invasion. He named his settlement ‘York' and moved the provincial capital here from the vulnerable border village of Niagara.

York grew slowly to only 720 people by 1814 and faced numerous blows in its early years, including American attacks and occupations during the War of 1812. Nevertheless, the settlement expanded quickly after 1815 because of its importance as the colonial capital, which also attracted institutions with province-wide interests, such as banks and schools. Additionally, it was geographically well positioned to serve the commercial needs of a newly-settling hinterland at a time of expanding trade and improving transportation. When the province incorporated the town as the City of Toronto in 1834 (to provide mechanisms to meet the needs of an urbanizing population), the community was Upper Canada's largest with 9,250 souls. This population continued to grow, reaching 30,775 in 1851 on the eve of the railway era. However, various tribulations threatened the city: the economy suffered serious downturns at various times, rebellion divided Toronto violently in 1837-8, cholera ravaged the population in 1832, 1834, and 1849, and typhus struck in 1847-8. Yet, b y 1853, the year the first trains pulled out of Toronto, a recognizably modern city had taken shape, with distinct residential and commercial neighbourhoods, gas lighting, piped water, and such notable public buildings as St Lawrence Hall and St James' Cathedral.

Industrialization, beginning modestly in the mid-19th century, expanded greatly after Confederation, and contributed significantly to shaping the city's environment and prosperity. By 1901, the industrial, commercial, financial, and institutional centre had a population of 208,000, which rose to 667,500 by 1941. During these years, Toronto began to compete with Montreal as the nation's premier centre, not only economically, but also culturally, as exemplified by the founding of the Royal Ontario Museum in 1912 and the Toronto Symphony in 1922. Toronto's population eventually surpassed Montreal's in 1976, by which time the city had become Canada's most important economic and cultural engine.

As late as the 1940s, Toronto's population was largely Protestant (72 per cent in 1941), and fundamentally British (78 per cent, but mainly Canadian-born). As might be expected given these statistics, the world wars saw Torontonians flock to the colours with particular fervour compared to other parts of Canada. At the same time the great 20th-century conflicts

contributed to dramatic increases in the city's economic, industrial, and technological enterprises as well as in breaking down social barriers such as the presence of increasing numbers of women in the workforce. Torontonians faced numerous other challenges during the 20th century, ranging from the poverty suffered by many families across the generations to the shorter-term disaster of the Great Depression.

A great shift in the spirit of the community began with the numerous waves of immigrants after 1945. By 2001, Toronto had become one of the most multicultural cities on the planet, where 152 languages and dialects were spoken in an atmosphere of comparative harmony. According to that year's census, more than half of Toronto's 2.5 million residents were born outside Canada, and a million people belonged to visible minorities. These post-war decades also saw the compact city of 1945 burst its boundaries like other North American cities to consume some of Canada's best farmland, both within Toronto's ultimate 632-square-kilometre boundary, and far beyond into the bedroom communities of Ontario's ‘Golden Horseshoe.'

Today's Toronto is a large and complex urban centre. Like any similarly large city it faces important challenges and competing opinions on how to face them. At the same time, Toronto continues to flourish as a tremendously exciting city, embracing a strong and prospering economy, rich cultural underpinnings, and retaining its long heritage as a comparatively safe, orderly, and inclusive community, where working and living conditions are among the very best to be had on the planet.

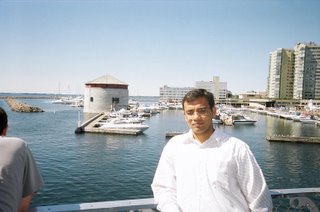

The 1000 Islands region of upstate Southeastern Ontario and New York near to Kingston. This site is intended to be your one stop for information on the 1000 Islands region and its local business. The Thousand Islands is a pristine resort community surrounded by Lake Ontario, the Adirondack Mountains and the mighty

The 1000 Islands region of upstate Southeastern Ontario and New York near to Kingston. This site is intended to be your one stop for information on the 1000 Islands region and its local business. The Thousand Islands is a pristine resort community surrounded by Lake Ontario, the Adirondack Mountains and the mighty St. Lawrence River.The St. Lawrence River, flowing in from Lake Ontario becomes in the course of a few miles, so wide and so full of islands that it was called the Lake of the 1000 Islands. To the Indians it was known as “Manatoana” or Garden of the Great Spirit. As a vacation paradise it is world renowned. The river, 15 miles at its source, gradually narrows to five miles in width, and the islands over 1800 of them, vary in size from mere points of rock to those of several square miles in area. They extend from Cape Vincent

St. Lawrence River.The St. Lawrence River, flowing in from Lake Ontario becomes in the course of a few miles, so wide and so full of islands that it was called the Lake of the 1000 Islands. To the Indians it was known as “Manatoana” or Garden of the Great Spirit. As a vacation paradise it is world renowned. The river, 15 miles at its source, gradually narrows to five miles in width, and the islands over 1800 of them, vary in size from mere points of rock to those of several square miles in area. They extend from Cape Vincent to Ogdensburg, a distance of 50 miles. The 1000 Islands-Seaway Region boasts some of the very best sportfishing opportunities in the nation all year-round whether you're a novice or an avid angler. It's not unusual to see a professional bass or salmon tournament underway on the St. .

to Ogdensburg, a distance of 50 miles. The 1000 Islands-Seaway Region boasts some of the very best sportfishing opportunities in the nation all year-round whether you're a novice or an avid angler. It's not unusual to see a professional bass or salmon tournament underway on the St. . Lake Ontario is known

Lake Ontario is known  worldwide as a mecca for salmon, brown and lake trout fisherman, and the bass and pike fishing in the St. Lawrence, Black, Salmon, and Oswego rivers is great. The muskie fishing in the St. Lawrence River and the walleye fishing in Oneida Lake are legendary. The Eastern Lake Ontario tributaries also form one of the finest winter steelhead fisheries in the Northeast

worldwide as a mecca for salmon, brown and lake trout fisherman, and the bass and pike fishing in the St. Lawrence, Black, Salmon, and Oswego rivers is great. The muskie fishing in the St. Lawrence River and the walleye fishing in Oneida Lake are legendary. The Eastern Lake Ontario tributaries also form one of the finest winter steelhead fisheries in the Northeast

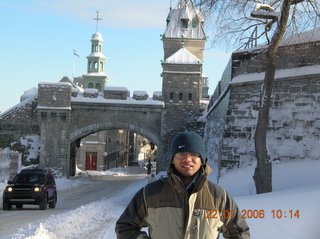

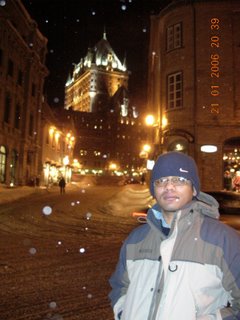

Québec City was under French rule between 1608 and 1759, except for the period between 1627 and 1632, when the Kirke brothers controlled the city.

Québec City was under French rule between 1608 and 1759, except for the period between 1627 and 1632, when the Kirke brothers controlled the city.

YourNiagara Community Portal which involves municipalities within the Niagara Region. It provides information to the residents of the Niagara Region with information, links, business information and mapping for the entire region. Visit www.yourniagara.ca to view the portal.

YourNiagara Community Portal which involves municipalities within the Niagara Region. It provides information to the residents of the Niagara Region with information, links, business information and mapping for the entire region. Visit www.yourniagara.ca to view the portal.